75 years after it was last performed, there is no known surviving score for Frederick May's Symphonic Ballad, but through a careful examination of the remaining orchestral parts, MARK FITZGERALD has at long last been able to bring the music back to the concert stage.

Born in 1911, Frederick May began his music studies in Dublin with John Larchet and Michele Esposito at the Royal Irish Academy of Music. In 1930 with the aid of a scholarship from the Feis Ceoil he enrolled at the Royal College of Music London, where his teachers included Ralph Vaughan Williams. A travelling scholarship from the RCM enabled him to study with Egon Wellesz in Vienna in 1933. By 1935 he had returned to Dublin and at the end of the year was appointed Director of Music at the Abbey Theatre, a job which mainly consisted of directing from the piano a trio which provided entertainment for the audience during the intervals of plays. From 1938 onwards he suffered from severe mental illness and otosclerosis which caused deafness and tinnitus and as a result May effectively abandoned composition in the early 1940s with only one further original work Sunlight and Shadow written in the 1950s. May’s compositional output is therefore very small but the String Quartet he composed in 1936 has always been seen as one of the seminal compositions in Ireland due to its modernity relative to other pieces composed in Ireland at this time.

In terms of orchestral music May’s output consists of the Scherzo (1933), Symphonic Ballad (1937), Spring Nocturne (1938), Songs from Prison (1941), the Lyric Movement for Strings (1942) and the late Sunlight and Shadow (1955). A CD of these works with the exception of the Symphonic Ballad and the Lyric Movement was released on the RTÉ Lyric label in 2011. The Contemporary Music Centre has some poor quality archive recordings of the Lyric Movement, a piece which was last performed in the 1980s, but I could find no trace of performances of the Symphonic Ballad. The fact that this piece was composed directly after the String Quartet made it particularly intriguing. Did the work reflect the language of the quartet or did it use the less chromatic language of pieces such as Spring Nocturne. Furthermore, why was the piece never performed?

May’s papers are housed in the Trinity College Manuscripts and Archives Research Library and perusal of the catalogue provided the answer to the latter question. The full score of the Symphonic Ballad is missing. Consultation with the RTÉ library and several other sources also drew a blank. Piecing together the history of the work, it was composed for the Belfast Wireless Symphony Orchestra (later the BBC Northern Ireland Orchestra) and the premiere was conducted by E. Godfrey Brown on 30 August 1937. Files in the BBC archive revealed that the work was given a broadcast performance on Radio Éireann on 4 September 1941 as part of a programme featuring compositions by May including Spring Nocturne and the songs Communion, Irish Love Song, The Finch and North Labrador. In a letter from the late 1940s May, replying to a proposal from Aloys Fleischmann to perform the Scherzo in Cork noted: ‘There’s a thing of mine called Symphonic Ballad which hasn’t been done for a good while, but maybe it’s a bit long.’ At some unknown point after this the score was mislaid or perhaps sent to a conductor or orchestra and never returned.

What has survived among May’s papers in Trinity is the set of orchestral parts used in the 1941 broadcast performance— One of the bassoon parts is annotated with the words ‘Sept 3 1941 R[adio] P[erformance]’. I decided in 2015 to use these to reconstruct the score in order to throw further light on May’s development as a composer. As I progressed with this work it became clear that the process was going to be far from unproblematic. Either the parts were copied rather carelessly from the full score or (quite plausibly judging by other surviving manuscripts) May’s handwriting in the lost full score was difficult to read. Whatever the cause the parts contained an enormous amount of mistakes which gradually became evident as work on the reconstruction proceeded. Some of these were easy to spot. The parts did not have bar numbers but they had rehearsal letter cues. Frequently the amount of bars of rest in various parts was incorrect, but if one reached a new letter and one part either had not yet reached that letter or was a few bars shorter than the other parts, it was easy to trace this back to a lack of or over-abundance of rests. And so what had looked like canonic passages became unison passages and particularly odd harmonic relations resolved into something more expected. Passages with unison writing or octave doubling threw up other anomalies as occasionally one would find one note different in a line shared by two instruments. It was then a matter of deciding which was correct based on the patterning of the line or previous iterations of an idea. At other points particularly unlikely momentary dissonances could be attributed to misreadings or faulty transpositions in the brass parts. Almost every page of the sixty-four page score contained several mistakes that needed to be corrected. Use of dynamics was also somewhat haphazard in the original parts while phrasing was frequently ambiguous.

A further complication was created by the circumstances of the 1941 performance. RÉ had not got enough wind and brass musicians for the piece and so important passages in the missing parts were redistributed among the other orchestral parts. Therefore passages were crossed out and redistributed passages were written in over rests or in the margins of the parts. All of these changes had to be eliminated to get back to the original version of the score. The one conclusion one can come to about the 1941 performance is that between the inadequate orchestral resources available and the poor quality of the parts it must have been absolutely terrible. Interestingly a BBC listener’s report for this broadcast survives and while one must make allowances for the poor reception in London his suggestion that Spring Nocturne sounded like the first section of The Rite of Spring and that the Symphonic Ballad sounded ugly and reminiscent of Sibelius ‘at his grimmest and most uncompromising’ would tend to bear out that impression.

Recently I have located an early draft of the score entitled Sinfonietta. As was normal practice for May there are a number of significant differences between this and the final version of the piece. However, the choice of title and the later change to Symphonic Ballad is interesting. Unlike Spring Nocturne which May described as being in the same genre as the idylls of Butterworth and Moeran, it would suggest that in this composition May was attempting to achieve a more symphonically wrought argument, a trait which would bring it closer in idiom to the String Quartet than the later orchestral pieces.

The initial theme of the piece is a fairly mundane idea given first to cellos:

Figure 1: May, Symphonic Ballad, initial theme (b.1-4)

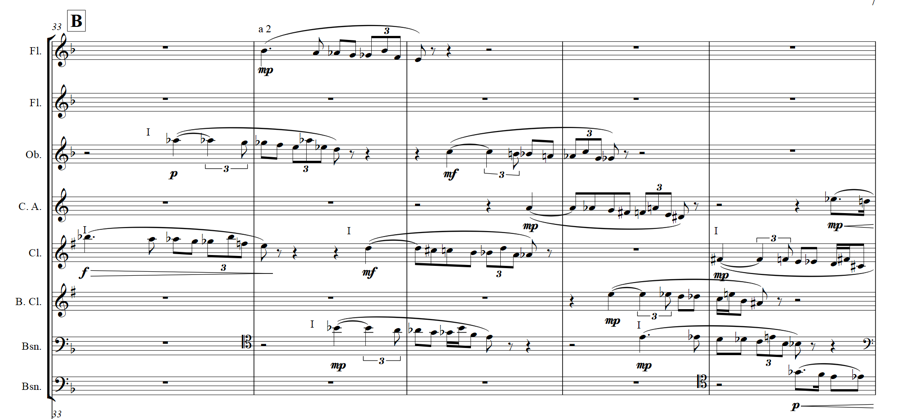

Against ideas derived from that are pitted descending chromatic lines in the wind instruments which are to be an important device throughout the work:

Figure 2: May, Symphonic Ballad, descending chromatic lines (b.33-37)

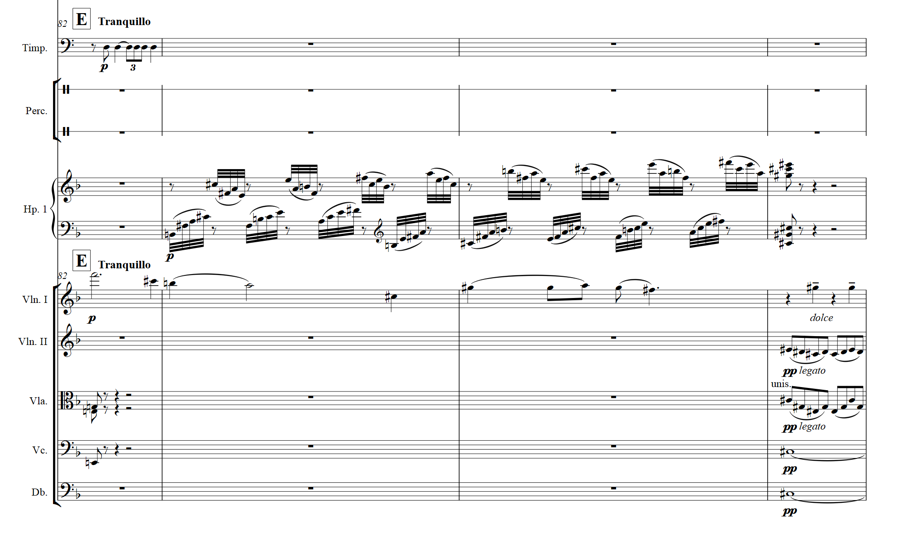

By contrast with the urgent opening part there follows a more pastoral section featuring solo violin and harp:

Figure 3: May, Symphonic Ballad, use of solo violin and harp (b.82-92)

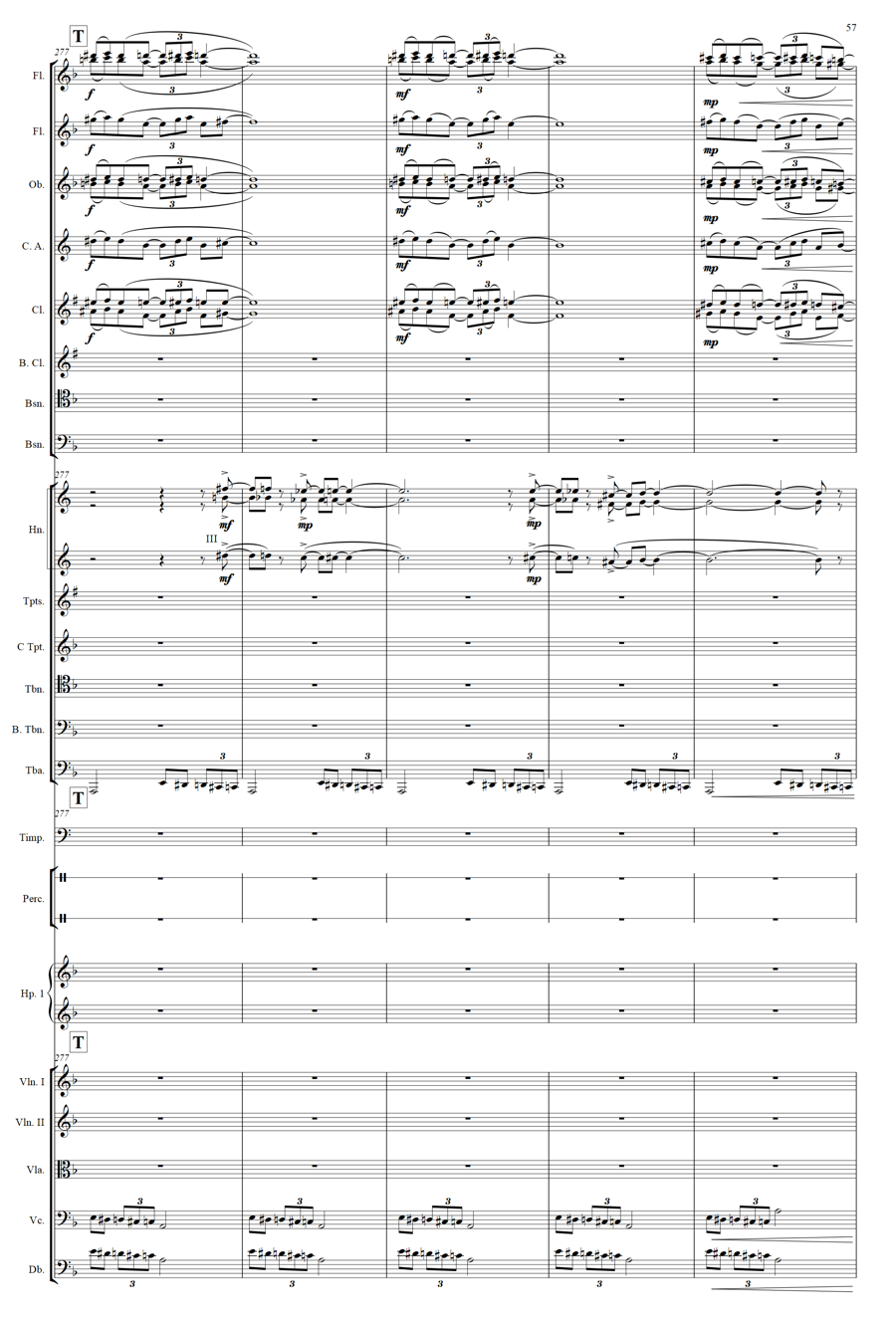

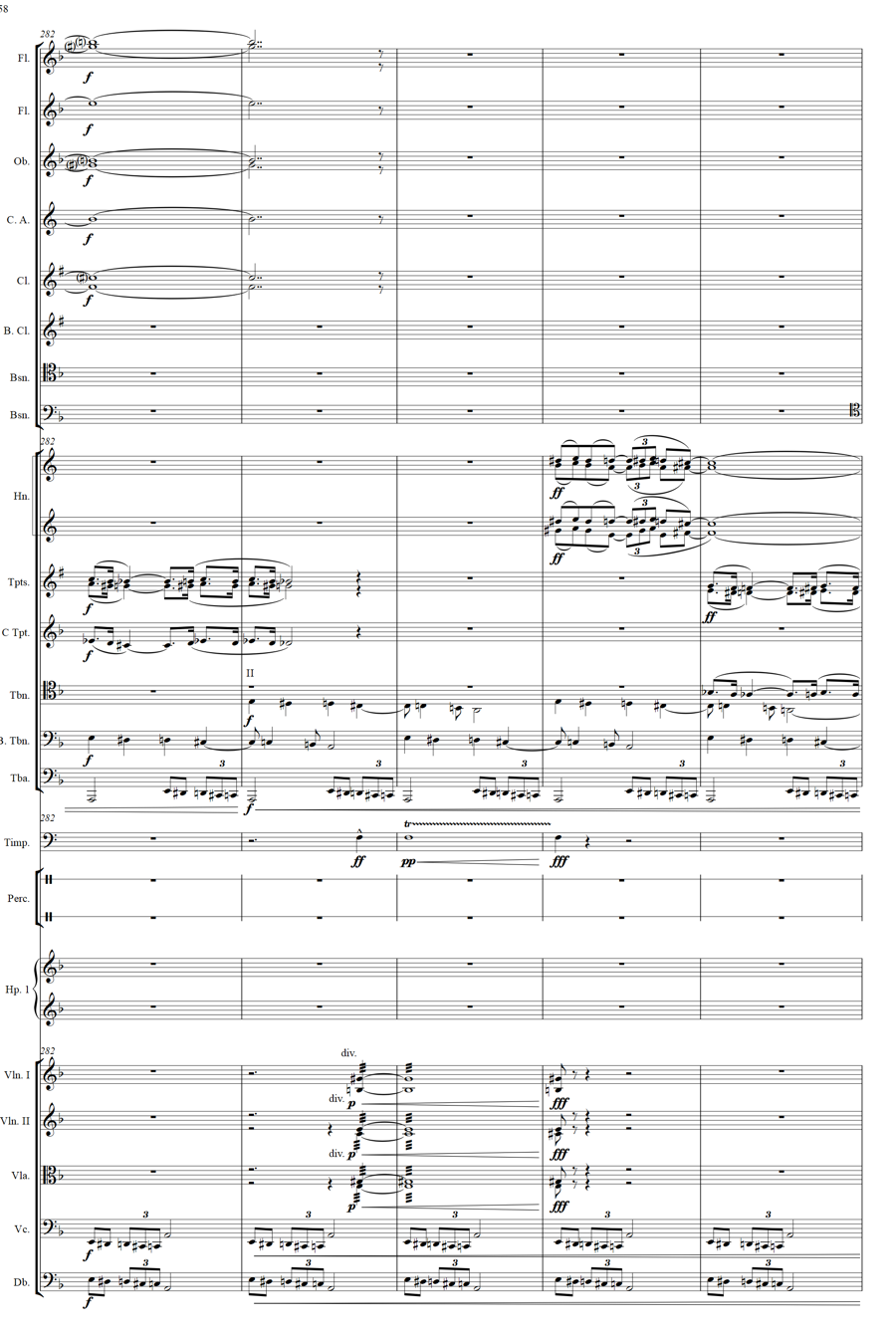

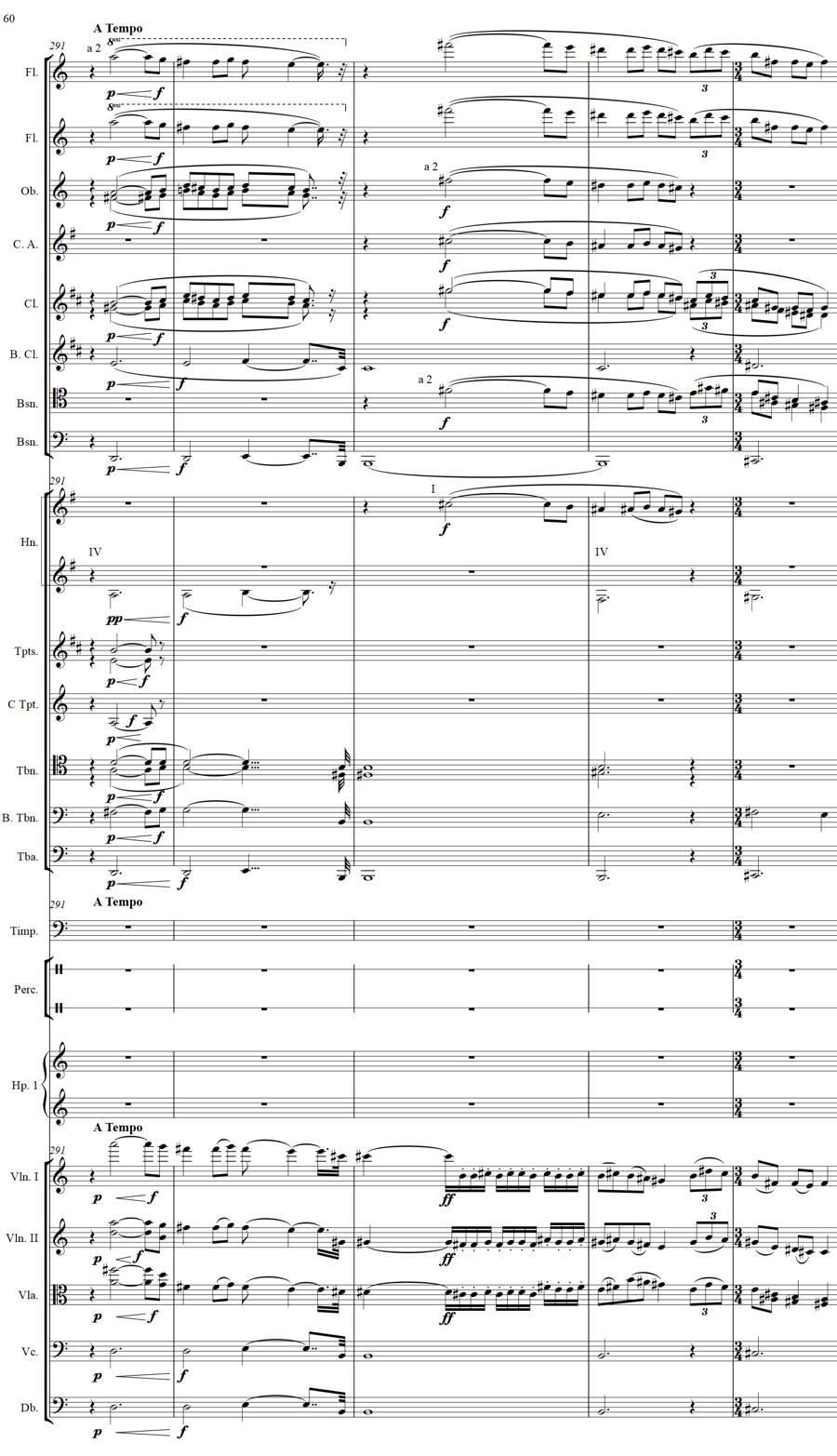

A repeated pattern on side drum leads into the developmental part of the piece which features the most adventurous writing of the composition. Interspersed between passages in which there are statements of principal ideas with a clear tonal anchoring are more restless chromatic sections derived from the chromatic lines of the opening. The sense of uncertainty is emphasised by May’s tendency to modulate quickly by a semitone. This is not only used for short term movements but is frequently used for repetitions of larger sections of material—a tutti passage is heard and then after a short chromatic section is repeated either a semitone higher or lower. As the piece progresses, May increases the contrapuntal layering of ideas and also uses repeated figures to create denser textures at points of maximum tension:

Figure 4: May, Symphonic Ballad, contrapuntal layering and repetition of figures (b.277-286)

The Ballad concludes with a short section based on a transformed version of the pastoral violin theme from the second section:

Figure 5: May, Symphonic Ballad, transformed solo violin theme from Figure 3 (b.291-295)

Frederick May has long been seen as the most important figure in Irish composition from the first half of the twentieth century, an assessment that is based primarily on his String Quartet of 1936. The release of the RTÉ Lyric Label CD of orchestral music in 2011 gave a wider audience an opportunity to engage with a greater amount of his output while the release of a CD of May’s songs by DIT on 8 September 2016 will also help to illuminate the development of May’s musical voice. The performance of the Symphonic Ballad on 9 September will I believe play a particularly important role in our reassessment of May’s career. For too long discussions about May have focussed primarily on what he did not do rather than on what he did actually achieve. The Symphonic Ballad is a more cogently argued composition than either Spring Nocturne or Sunlight and Shadow which to date have been seen as his most important purely orchestral compositions. Its proximity to the String Quartet throws light on his compositional ideas at this point while also raising issues regarding how this changed in the following years.

The reconstructed edition of the Symphonic Ballad, to be performed at the National Concert Hall on 9 September at 20:00 as part of the Composing the Island festival, was made by Mark Fitzgerald using material housed in the Trinity College Manuscripts and Archives Research Library by kind permission of the Keeper of Manuscripts Dr Bernard Meehan and facilitated by a Trinity College Long Room Hub Fellowship.

Musicologist Dr Mark Fitzgerald lectures at the DIT Conservatoire of Music and Drama. His research focuses on music of the twentieth century, particularly music in Ireland.

Header image with thanks to http://www.tcd.ie/library/manuscripts/blog/tag/frederick-may/